Many people feel overwhelmed by the prospect of starting to write an academic paper. At this point it can be useful to remind yourself that writing is a process made up of many different phases. Most texts are revised several times before they are finished. This section provides tips on how you can make this work easier.

Your writing process

An important starting point for successful writing is finding your own way of writing: your writing process. Therefore, ensure that you write about something that engages you within the area you are expected to write about. Does a subject prompt you to pose the questions: “How?” and “Why?” If so, you have probably found something that is worth writing about. It is the curiosity and passion for discovery behind these questions that is the basis for most of the research carried out in the past. So, adopt the researchers’ approach – proceed from your own thoughts and experiences. What engages you? What are you interested in? Take the opportunity to develop your own ideas, test your prior knowledge and learn more about what made you want to pursue your studies!

The overall writing process

The writing process consists of all the work you do, from thoughts and outlines to finished text. Depending on where you are in the process, you will notice that the texts you write look different. Some of them will deviate from the requirements for clarity and precision that are fundamental for academic texts. It is important to remind yourself that these requirements apply to the finished text. The development of your thoughts and text can require that you write in a less formal way.

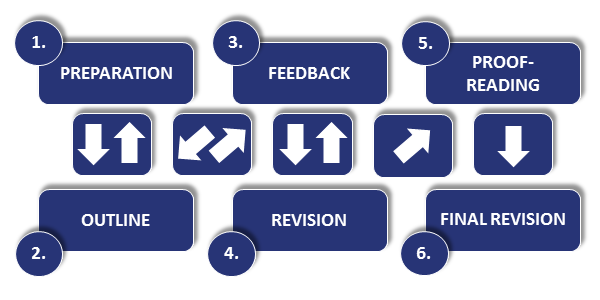

The six phases of the writing process

A simplified model of the writing process is illustrated below. It is important to remember that academic writing is not a linear process – this is illustrated by the arrows in the model. It is common, for example, that you need to go back and supplement the preparation, produce new drafts or perhaps amend your aim. It can also be the case that you need to revise your text several times. Give yourself the time to go through all the phases of the writing process, from the first creative steps when you investigate what you are going to write about to the final steps when you make the text as reader-friendly as possible. To find time to do all this, it is important that you start writing as soon as you can.

1. Preparation

Preparation consists of:

- analysing the assignment and the language situation and deciding what you are going to write about

- starting work on your aim and research issue

- thinking about the type of material you need

The first thing you need to do is to analyse the assignment and the language situation. Often the circumstances are stated in the assignment you have received, but in other cases it is up to you to analyse what is most suitable for the assignment. After this, formulate a plan for your writing. With a plan for your writing activity and how the text is to be structured, your writing will more straightforward and logical. Remember that this preparation is the framework for your text!

Analysis of the assignment and language situation

To analyse the assignment, you need to ask the following questions:

- What type of text is to be written?

- Who is the intended reader?

- What shall I write about?

What type of text is to be written?

The type of text you are to write determines the degree of focus you need to devote to the text’s various parts. The type of text also steers how formally or informally you can express yourself. Is the text of an argumentative nature? In this case, it is important that you structure your text so that your arguments are clear for your readers. Or is it a scientific report, a review or a commentary? If so, different guidelines apply for these types of text. Therefore, you should first and foremost identify the type of text you are to write. The common aspects of all academic texts are found in the section Writing.

Who is the intended reader?

The intended reader provides a hint about the level of language you should maintain and the reader’s expected level of prior knowledge. It is most common in the writing of academic texts to write for a specialist in the subject – someone, just like you, who has considerable prior knowledge, but is interested in finding out more. If it is not apparent from the assignment who the reader is, we recommend that you imagine a reader with about the same level of education as yourself – one of your fellow students, for example.

Many inexperienced writers make the mistake of writing for their teachers or for themselves. A common problem with the resulting text is that the writer neglects to explain certain terms, which are familiar to the writer or teacher.

What shall I write about?

Once you have a clear idea of the assignment, part of the preparation work has been done. The most important question to answer is: What you are going to write about? Sometimes this is apparent from the assignment, but in large, independent projects, it is down to you to answer the question. It is important that the subject you choose is adapted to the assignment in terms of scope and subject area. By reformulating your subject to an aim, a research issue and/or several research questions, you make it easier for yourself and the reader to identify your main area of interest. You can read more about how to do this in the section, Aim, issue and research questions – delimiting the subject matter.

It is important to allow time for working out what you are going to write about. It is also important not to be afraid of changing your mind along the way. Few writers adhere completely to their aim and research issue during the process. Therefore, do not spend too much time trying to come up with the perfect aim or research issue. Be satisfied with one that is sufficiently clear, focused and complex to allow you to start the work.

Another important point is to save all the sources and all information you find and may possibly use in the work. It is a good idea to save a copy of texts you find on the internet, as in the worst case scenario these might have been removed the next time you search for them. Collect all information on your source in a single document, for example, and it will make your later work on source references much easier. You can find out more about how to save and handle references in the section, Managing references.

Aim, issue and research questions – delimiting the subject matter

When you have chosen a subject, the next step is to delimit the subject matter according to the assignment. Going through and sorting the gathered material hopefully awakens thoughts on something particularly interesting that you can build on in your project. In order to identify this, use your aim, issue and research questions.

It is not altogether self-evident where the dividing lines are between these three terms, or if you need to use all three. Sometimes other terms are used such as “presentation of a problem”. If it is not stated in the assignment instructions, it is a good idea to discuss what is required with your supervisor or someone else familiar with the subject area you are writing about.

If you use the aim-issue-research questions approach, it is important to consider that all the ways of describing your study must be in agreement. They all have the same function: to delimit the subject area you have chosen and tell the reader what you have done.

In general, it can be said that aim and research issue are somewhat broader terms, intended to give an overall view of the work you have done. If required, these can be broken down into one or more research questions, which further clarify what the text is about.

Things to consider when formulating your aim:

- The aim should always to be written in the present tense, namely “the aim is”, not “the aim was”. This is because the text is intended for a reader, and the reader always meets the text in the present. All text about the text in question shall be written in the present tense.

- The aim should not be normative – state that you want to change something. In research texts, the aim should always stem from your curiosity – how and why something is a certain way. However, in the discussion section you can discuss what your conclusions mean, and propose changes or point to the implications of the activities or context you investigated.

Things to consider when formulating a research issue:

- “Issue” is not necessarily a negatively charged word within science. It is perhaps fairer to call it a gap in our knowledge. Research issues often concern a writer wanting to examine a niche in a subject area that has not been previously explored, or to compare previous studies to see whether interesting connections can be found.

Things to consider when formulating research questions:

- Research questions are a type of question you pose to your text and to your research material. Do not confuse research questions with questions you have posed as part of your research. If, for example, you have interviewed people or carried out a survey, you have no doubt posed a number of questions. These are not research questions.

Research issue for a degree project

Are you going to write for a degree project and find it difficult to find a problem formulation? Listen to some good advice from Ulrica Skagert, PhD in English and Quality Developer at the Blekinge Institute of Technology:

Material

During your preparation work, you should think about how you are going to find material for the text. Does the type of text and aim of the text require you to conduct a quantitative survey, or are in-depth interviews more suitable? Certain assignments perhaps do not require some form of material gathering, but rather the use of your own memory.

You can get assistance concerning searching for information at your library. The library has subject and search guides on the internet and you can also get guidance from staff.

2. Outline

When you have conducted a basic analysis of the assignment, it is time to draw up a plan for the continuing work. A suitable starting point is to produce an outline of the text. Perhaps you already have one or more free writing texts about what you want to write about? Use these!

Are you finding it difficult to get started? Are you getting stuck in the details of the text? Here are some tips on avoiding writer’s block: Symptoms and Cures for Writer’s Block.

Produce a rough outline

It is often a good idea to start creating a framework for your text at an early stage. A good strategy is not to be satisfied with obvious headings such as introduction, method, analysis, discussion and so on. Try to use headings with content linked to what you are actually writing about. This will make it much easier for you later, when it is time to fill the various sections with content.

Depending on the topic you are writing about, it is important to be aware of the requirements set for the finished text’s format. Within the humanities it is common to have content-related headings, but these are not used, for example, in the sciences, engineering and medicine. However, this does not prevent you from using headings as a way to get going and progress in your writing process. Remember to ensure that the final text complies with the requirements relevant for your subject area.

Working on the headings is very likely to make your writing easier, which you will notice, for example, when you start writing the introduction and suddenly get an idea that is more suitable for the method or discussion chapter. If you have already created a framework, it is easy to add comments or create a new subheading in the right place, and then go back to the introduction without forgetting the smart idea that came up during the writing session. Writing is a learning process in itself – while you write, your thoughts become clearer, and new thoughts spring to mind.

In the section, Parts of an academic paper, you will find more detailed tips on what should be included, and the style to follow, in the various parts of the academic paper.

Creating a text

Get inspiration for your writing process from the presentation, “Structuring a text around the three-part essay” by Dr. Ellen Turners from Lund University (5 min):

Start to express yourself

When your framework is ready, it is time to start writing the text you are going to submit. If you have previously made notes or have passages of free writing, you can begin to place these under the respective subheadings. However, bear in mind even at this stage that the finished text is to be communicative, so adapt the content to your readers.

3. Feedback

The next stage in the writing process is to get feedback on your text. This is something that many writers worry about. If you are worried, try to remind yourself that feedback is a tool for helping you to progress, not criticism of you personally or of you as a writer. In general, we are bad at letting our texts go, and at giving and receiving feedback on what we have written. However, the only way we can improve is to practice. Through practice you will also notice that you get more benefit from the feedback you receive.

Remember that you are responsible for the text. You don’t need to change everything according to people’s objections. On the other hand, you must have a good argument for not making the changes.

It is important to work on your capability to see your text from the outside, as a reader – to give yourself feedback. One of the basic prerequisites for achieving this is to let the text rest, at least for one day. Using this approach creates distance from the writing and you can see the text with new eyes to some extent.

4. Revision

In most cases, getting feedback and revising your text is in several stages, and the number of revisions rises with the scope of the assignment. What you primarily need to think about in the revision phase is that you are now in the process of creating a presentation text. Therefore, refer to the right-hand column of the Dysthe, Hertzberg och Løkensgard Hoels model. The text is now oriented towards explaining to others rather than explaining to yourself. If you have used personal language, you should now make it more formal. You can find out more about how to do this in the sections, Creating cohesion and Academic language.

In this phase of the writing process, you also find yourself in a creative process. It is therefore important that, as you start working on making the text communicative, you also give yourself time for rethinking and developing thoughts that have emerged in the course of the project. Do not spend too time much on writing perfect sentences, as you risk getting stuck in the details.

Things to consider during the revision phase:

- Do the main thoughts in the text come across clearly on a first reading? A text shall act as communication to the reader. If it is hard to access and understand the text, the reader’s impression of the text is impaired.

- Does the text follow a structure that supports the type of text and clarity? Do any paragraphs or sentences need to be moved?

- Does the style of the text comply with the requirements of the task and the academic context it is written in?

Are you noticing that you are not making any progress? Put the text aside and have a session of free writing. It is likely that this will produce ideas to help you solve your problem.

5. Proofreading

When you feel that you have included everything that is required, that the text has a theme, and you have used the language and format appropriate to the assignment you are to write, then it is time to proofread the text. Now you have the chance to find errors and ambiguities that can be easily corrected.

Things to consider when proofreading:

- Is the spelling and grammar correct?

- Are your commas, full stops and paragraphs placed correctly?

- Do you understand all the words you are using? If not – double check with the literature. If necessary, change the words that are incorrect or inappropriate.

- Have you used the right typeface, types size and line spacing throughout?

- Are the headings in a logical order? Do they match the table of contents?

- Are the references consistent with the reference system you have chosen?

If possible, get help from someone else to proofread your text. It is easy to have a blind spot for your own errors and read into the text what is not actually there.

If you have the chance – print out your text. Most people find it easier to read text on paper. This also stops you from changing details in the text while you are reading, which means you have a greater possibility to see the text as a whole.

6. Final revision

Go through your proofreading notes, from beginning to end. Also check that the page numbering is correct, that the title page, if you are expected to have one, follows the guidelines that apply, and that references and appendices are included.

Before you submit the text, use the word processor’s spelling checker. Every spelling mistake or grammatical error is an obstacle for the reader and adversely affects the reception of your message.