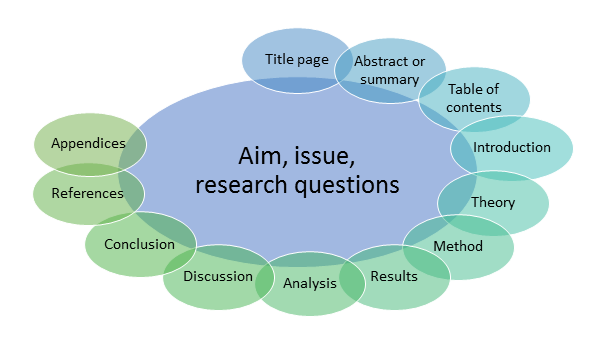

In order to make academic texts easy to read and their contents easy to find, they usually follow a predetermined structure. Although this structure may differ slightly depending on the subject, the objective remains the same: to make it easy for the reader to find what they are looking for in the text. The structure’s role in this is to be the very framework that holds all the different parts together. Regardless of how advanced your text is, the various parts of the text must relate to each other so that the reader can follow your line of thought. In addition, each part serves a specific purpose, and the way you construct them is what creates cohesion.

In this section of the Writing Guide you will receive advice on the overall components that should be included in academic papers and reports. You will also receive a description of the various functions of the different components. To learn more about creating linguistic structure in terms of chapters, paragraphs, and sentences, see Creating cohesion.

Depending on the scope of the assignment and your current level of study, the various parts of the academic paper may be more or less important. Therefore, always follow the instructions for the assignment when planning your writing. Under Resources, you will find templates and other resources from the higher education institutions involved in the development of Writingguide.se.

Well-structured academic papers share certain characteristics:

- all asked questions have been answered or addressed

- the reader understands where the writer is going

- all accounts appear to be relevant to the whole

- the theory you have described is used to analyse and interpret data

- the method is described well and corresponds to your research issue

- the results correspond to the aim

- the discussion links empirical data, theory and method together

- the conclusions are justified by the results of the discussion

Academic papers are to be written according to an established structure, which may differ, depending on the subject. The IMRaD model (Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion) is usually applied to subjects in the fields of science and engineering. In social sciences and humanities, the structure is freer.

Structuring a scientific text

For a description of how to structure your paper according to the IMRaD model, see a lecture “Academic Writing: IMRaD” by Dr. Satu Manninen from Lund University (11 min):

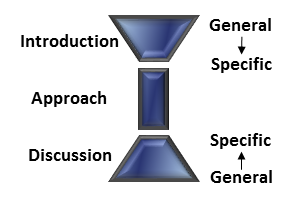

The “spool of thread” model – a holistic perspective on your paper

The “spool of thread” model can suitably be used as a basis for writing your paper. The model describes a holistic perspective on academic papers, in which you, the writer, begin by writing in general terms, gradually become increasingly specific, and conclude by explaining what, specifically, you have arrived at in general terms. Simply put, you start big and then you go small, and conclude by showing how the small – the specific topic you have chosen to write about – affects the big.

The “spool of thread” model demonstrates how important it is to write not only about what you are interested in, but also to put what you write into a context that can be understood by others. Again, the focus should be on communicative aspects of writing.

Title page

Not all assignments require a title page, but when they do, it is good to know that most higher education institutions offer templates or instructions for designing your title page. Remember that the title page is to provide information instantly to the reader regarding the title, author and type of work. It is also to provide information concerning your study programme and the higher education institution you are attending.

Abstract or summary

An abstract or summary provides a brief account of the main content of an academic paper. The purpose of the summary is partly to generate interest, and partly to present the main issue and key results. Most importantly, the summary is to capture what the paper is about. Shorter papers usually do not require a summary.

The summary is best written when you have almost completed your project. Only then will you know what you have actually written. A good idea is to work on a draft summary alongside your paper, and revise it as you go along. The summary is a difficult text to write, as it is to cover a lot of content in a small space. But, that is also why it is a useful text to work on – it forces you to formulate what your project is about.

Table of contents

In more lengthy texts, e.g. papers, you may be required to include a table of contents. Do not underestimate the importance of this! Instead, see it as an opportunity to give the reader an idea of what the text is about at an early stage. This is done by formulating headings and subheadings that briefly explain the content of each chapter. For more information on formulating headings, see Outline in The writing process section.

Most word-processing programs offer templates for tables of contents, which the program will subsequently create for you. By using these, you ensure that the table is correct and looks good.

Introduction

The introduction often contains:

- a background to the topic

- aim and issue

- a description of the outline of the text

An introduction is necessary in order to engage the reader and acquaint them with the subject, as a soft-start and orientation. The aim of the academic paper is usually included in the introduction, but sometimes, especially in more lengthy texts, the aim has its own subheading. In the introduction, you can also provide a background to the topic and an overview of relevant published research in order to place the topic in a wider context. The introduction is intended to lead to the research issue of the paper.

Instead of writing that you are interested in the subject, describe why it is interesting. The focus is to be on the subject, not you as the author.

The introduction is not something you simply write at the beginning of your project and then lay aside. We recommend that you return to the introduction throughout the writing process to see if something needs to be added, removed or rephrased, as this section is to reflect the entire paper, including your discussion and conclusions. It should be possible to link any drawn conclusions to what you wrote in your introduction.

Background

This section is to give the reader the necessary background information in order to understand the context in which your study was conducted. Depending on the scope of the text, the background is sometimes part of the introduction and sometimes included as a separate chapter. If you are unsure of what applies in your case – talk your teacher or supervisor.

In the background section you can, for example, provide a historical overview and explain important concepts. For instance, if your paper is on teaching and learning, perhaps you will want to account for relevant policy documents (the Swedish Education Act, curriculum, etc.). In contrast, if the topic of your paper concerns medical science, you may want to account for certain medical terminology or concepts.

In the background section – or in a separate chapter – you must also include a presentation of previous research in the field. In this presentation, you are to describe any research of relevance to your paper, for example, similar studies or research findings which can be related to your results. Furthermore, you must justify why the selected research is relevant to your own study.

The best way to learn how to write a certain type of text is to read others’ texts of the same type. Ask your lecturer for examples of texts, or search for them yourself in DiVA, where you can find student papers as well as research publications which have been produced at a large number of Swedish higher education institutions.

Aim and Issue

The aim and research issue are the very essence of the introduction. Everything you write in the introduction, and by extension in your paper, must therefore be related to the aim. You may need to break down the issue into one or several research questions. Read more about how to formulate the aim, research issue and research questions under Aim, issue and research questions – delimiting the subject matter in The writing process section.

Describing the outline of the text – metatexts

One way to make it easier for the reader is to describe the structure of the paper in the introduction. This description is commonly referred to as a metatext – a text about the text.

The Writing Guide provides several examples of metatext, for example, at the top of the current page: “In this section of the Writing Guide you will receive advice on the overall components that should be included in academic papers and reports. You will also receive a description of the various functions of the different components.”

Metatexts serve as a guide for the reader, and can be used in all parts of your paper. For more information about metatexts, see Creating cohesion.

Theory

In an academic paper, it is important to present the theoretical framework and central concepts in the subject area you have chosen for your paper. Sometimes this is done in a separate chapter; other times it is included in the introduction or in the method chapter. If you are unsure – ask your lecturer what applies to your particular subject.

When presenting the theoretical framework you have applied, it is important that you, with reference to your aim, justify why the particular theories you selected are relevant.

Do not mistake the theory chapter with the part of the background section that concerns previous research.

Method

Describing your method is an important part of your paper, as this is where much of your credibility is established. In the method chapter, you are to account for what you have done, and explain why. You are also to describe how you collected your material and how you will analyse it, as well as any delimitations you have made.

The first thing to consider when writing the method chapter is whether the method you have chosen reflects the aim of your text. You must therefore explain your choice of method, and how you will apply it to address and answer your research issue or research question. You are also to describe how the choices you made have affected the validity and reliability of the study.

For example, if you have conducted interviews, what can you say about their validity and reliability? And if you performed a chemical experiment, how sure can you be that you used the right instrument? How confident can you be about the conclusions drawn on the basis of the method you have chosen? Was the selection sufficiently wide? Can the results be applied in general? By answering these questions, the different parts of the paper will be linked together. Specifically, the method chapter involves you showing that you have understood the practical meaning of the theoretical concepts you use in your text.

If your study concerns humans or animals, you also need to include an ethical discussion in your method chapter.

A methodological discussion is sometimes also included in the method chapter, in which you discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your choice of method in relation to your aim and research material. Other times, the methodological discussion is included in the subsequent discussion chapter.

Rather than writing that your study has high validity and reliability, you are to convince the reader that this is the case by describing your approach

Results, Analysis and Discussion

One of the most central parts of an academic paper is the reporting of results and subsequent discussion. This is where you present and analyse your empirical material, that is, your results. This could involve analysing your results in relation to previous research or reflecting on how well they relate to your theoretical framework. How well do your results hold up compared to previous studies? Are there similarities? Are there differences? How can your results be explained by theory?

There may be different combinations of the Results, Analysis and Discussion sections, depending on the subject and associated traditions. Sometimes, the analysis is carried out as a discussion; other times, it is performed in parallel with the reporting of results. This may affect which headings you use. For example, the commonly applied IMRaD model uses the main headings Introduction, Method, Results and Discussion, and, rather than writing the analysis as a separate chapter, it is usually included in the results section. However, this does not make analysis any less important compared to other models. All academic texts must include results, an analysis and a discussion.

What is the difference between results, analysis and discussion? One way to describe it is by comparing the academic paper to a puzzle. You start with the empirical material (the pieces of the puzzle); then, in the analysis, you examine every detail of this material to explain what the pieces mean and their function (connecting the pieces). Finally, the discussion is about interpreting and understanding the whole (the completed puzzle).

Things to consider when writing your results, analysis and discussion:

- In the results section, you are to present, communicate, account for, organise and categorise.

- In the analysis section, you are to interpret, compare, explain and contrast, on the basis of the theories you have chosen.

- In the discussion section, you are to summarise, generalise, justify, question, take a position and look to the future.

The results, or empirical data, are to be presented in a factual and objective manner. For example, if you have conducted an interview study, the results section is to describe what was found in the interviews, without interpreting or evaluating the interviewees’ responses. The empirical data must be presented in an accessible and transparent way. You are not to report what each interviewee said verbatim, but rather summarise the main features without omitting any important information.

You are welcome to divide the contents of your results section into different themes based on, for example, the research questions of the study, to allow a more comprehensible overview. Using metatexts is another way to make it easier for the reader.

Based on the theoretical perspective, in the analysis section you are to explain how your results are linked. It is important that you avoid personal opinions or introducing new theories. Everything you write must be linked to your aim and the theories and methods you described earlier. Also, be sure to support everything you write with clear references.

In the discussion section, you are finally to raise the analysis and results to a general level. You could, for example, start with the following questions: Can your results be interpreted in a different way? Can the results be applied in general? How do the results hold up in relation to comparable studies? What do the results mean for the practical activities reviewed in your study (if applicable)? What opportunities and needs for in-depth research do you see?

Closure – conclusions or summary?

There are different ways of ending an academic paper and these endings may vary in length. In certain subject areas, one or two sentences will suffice, while in others it may amount to several pages. Some papers require concrete conclusions, while in others it is more appropriate to end with a summary. In some cases, the summary and conclusions are part of the discussion chapter.

The most important thing to remember is that the research issue and research questions determine the appropriate way to end the paper. Also, remember that a research question which does not receive an unequivocal answer is also a valid result.

If you chose to end with a summary, this section is to be used to repeat the most important parts of the study, but preferably in a new way, for example, by placing them in a wider context. You should also place your paper in a broader perspective and point to a possible continuation. During the course of the project, new research issues may have emerged, as well as interesting literature which could be followed up, but this has fallen outside the scope of your project. If this is the case, you should write something about it.

Regard the conclusion as a reflection of the introduction. In the introduction, you described what you set out to do; in the conclusion, show that you succeeded. By tying your paper together this way, you help guide the reader to what you believe is your most important contribution to the subject of your study – you communicate your content and fulfil your assignment as an author of a scientific text.

List of references

Your conclusion/summary is to be followed by a list of references. Make sure that you apply the chosen reference system consistently. We recommend that you proofread your list of references several times – minor errors are easily missed. For more information on reference management, see Managing references.

Appendices

If your paper includes appendices, they are to be placed at the very end of your paper. If you have conducted a survey or interviews, the questionnaire and interview guide are to be included as appendices. If you are unsure about what to include as an appendix, consult with your lecturer or supervisor.